Naively, I thought that grief would involve tears. Sobbing, crying, wailing, weeping, bawling, whimpering, lamenting. That is the image of grief that I imagined.

Curiously, instead of tears, my grief reveals itself as exhaustion. Weariness, heaviness, bone-deep fatigue, tiredness like nothing I have felt before.

The exhaustion of grief is not merely the tiredness of sleep deprivation. It is an exhaustion that permeates my body, that weighs me down. Heed it I must; at times, it overrides my autonomy.

This exhaustion isn't new, but its weight is snowballing. Initially anticipatory grief and intense caring, it swelled when Neve died. I anticipated that it would start to get better, as time drifted and raced forwards. And yet, that is not the case. Life opens up and bustles, plates spin and the distance between Neve and I stretches. The simplicity of a busy life without the weight of grief somehow seems serene and agreeable, even when I know it is rose-tinted.

It strikes me that perhaps my grief exhaustion is compounded by the disconnect within me. No longer a connected whole, I feel fragmented. My body and my brain, divided, disjointed and jostling to lead. A further split, my conscious mind and my subconscious mind, at times oblivious to each other.

A tripartite division, three fragments. Each one experiences its own form of grief, independent of the others.

Conscious mind

Subconscious mind

Body

My conscious mind spends its time thinking and analysing, linking and connecting, talking and listening. This fragment of me doesn't understand why a particular date or day should be any more or less painful.

Take Mother’s Day, for example. To start with, a different date in the UK to that in Canada. A day where there is usually some recognition of me, as a mother, by those I mother. I appreciate the handmade cards and chocolates and this year, strangely enough, the raw vegetables, chosen especially for me. Yet not of such fundamental importance that I would be hurt if we didn’t do much; I know I am loved. So when others around me kept saying what a hard day it would be, I paid them too little regard.

My subconscious mind had its own perspective about Mother’s Day. It missed Neve, with an unexpected depth of sorrow. I yearned to see her, to talk to her, to hold her hand, to show her my paintings. My attention was pulled towards her bedroom, sure I heard her distinctive breathing. I almost expected her to call out for me.

From the depths, my subconscious reminded my conscious mind of past special days like this. I remembered the love and the thoughtfulness that Neve put into making cards, as well as the frustration and vexation. They needed to be just right; she had exacting standards and high ambitions. Thank goodness for the patience and wisdom of Neve’s carers and nurses, always up for helping her make these mementos of her love.

Strikingly, the abyss of my grief and sorrow was held within my body. A profound feeling of anxiety and unease, reinforcing the underlying exhaustion. Surely, this would have been the day for tears? Yet no, no tears came. How I long for these tears, this overt display of grief. I covet them, craving the lightness that trails behind tears.

I have so many questions for myself. I ponder binding my fragments together, asking for an explanation.

Which fragment of me is in charge of crying?

Who is holding the tears back?

Which aspect of me is stopping this desired grief reaction?

Are these tears being funnelled into the abyss of my exhaustion, rather than being allowed to see the light of day?

Would tears flowing, crying, would that relieve the exhaustion, even a bit?

As we move ever closer to the first anniversary of Neve’s death, with the not unexpected increase in exhaustion and anxiety, I want to know the secret to tears.

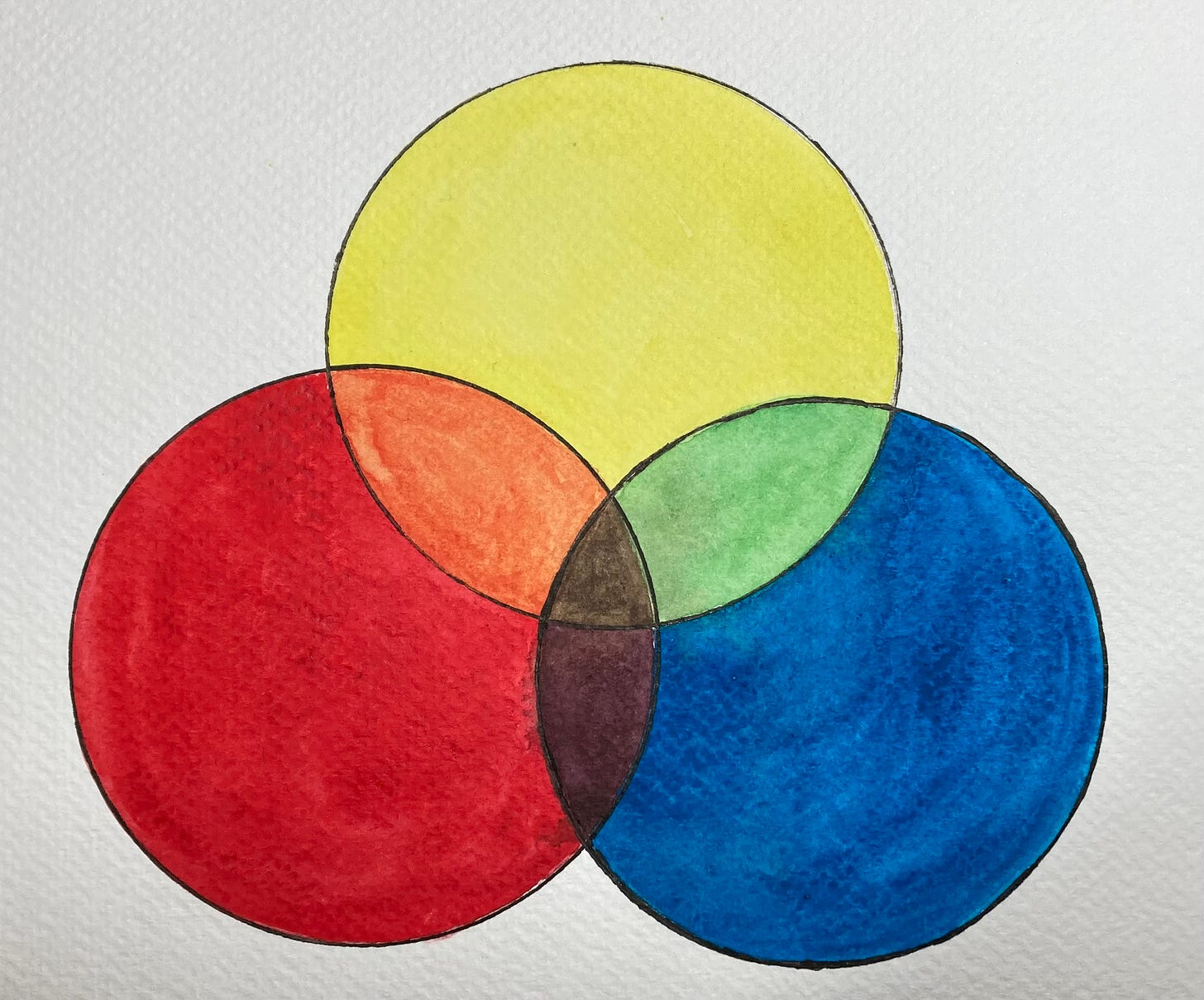

I revisit the disconnect, to further examine these three fragments. I picture a diagram, a map of me, three circles, very little overlap.

I think about all the occasions when my unconscious mind is adamant that I am crying or that the deep pangs of grief in my stomach are real. I subconsciously feel the battering of heartbreak, blows to my stomach, my body doubling over with grief, winded. My subconscious is steadfast in its knowing - it is resolute that the tears are there, that the pain is palpable. This is what I expected from grief.

The twist is just as tangible. I am not crying. I am not feeling the pain, not on this visceral level. I have not been winded, I am not and have not been doubled over. My conscious mind knows this with absolutely certainty. Even so, my subconscious mind is so compelling that I do stop to look in the mirror, searching for the tears that I am convinced I will find.

I am perplexed, eager for clarity about which aspect of me is in charge of my experience of grief. Previously, my brain and body worked together. I was not aware of their individuality, of their stubborn independence. It is as though they vie for control, eager to assert their own grief convictions on me. Do I need to sit them all down, tethered to each other and insist on a collaborative plan to allow the tears to flow?

Perhaps it should not be surprising that I am exhausted.

Sometimes I wonder whether I am really deconstructing inside, splitting, no longer a whole. Yet I am not on the outside of my body, I am not looking down on myself. I have been but not now. This isn't that. I am here, within me. I am grounded. Rather than a feeling of dissociation in space, it is the communication pathways that are muddled, an internal dissociation. Somehow, my conscious and subconscious minds are not communicating clearly with each other. In turn, the channels between my divided brain and my body are in a disarray.

I think back to a time, one of very few, when I found my tears, really found them. Last summer, for other reasons, I had returned to the hospital where Neve was treated and I sat where we used to sit, between appointments.

I watched videos of Neve, full of energy and vitality, hopping and jumping along the corridor where I now sat. I felt the profound absence of Neve’s vigour and spark. Somehow, this allowed a brief unity, within my otherwise fragmented self. I felt alone; in that moment, I was not mothering anybody. I noticed the weight of being Neve’s mother, of being the mother to a dead child. I had space and safety, the background faded and it was only me. I sat, isolated with my memories.

I cried that day. I wept and I sobbed. All of me, whole in that moment, felt my sorrow and my anguish. Looking back, I have visions of a three way summit, of a consensus. A subconscious mind, a conscious mind and a body, all slotting into place, all safe and secure in the setting, in the neutral coloured space of their overlap.

Eventually, the tears relented and I returned to the quiet hubbub of a hospital corridor. As I strolled off, there was no mistaking the weight that I left behind, on that wooden bench, in that corridor. Could others see me floating?

This temporary lightness is what I ache for, a palliation of the heaviness of my exhaustion. How then, how do I nurture all the fragments of myself to feel their griefs, simultaneously? How to set the scene, to allow for the safety and space for me to become whole again?

Pondering this framework to access my tears is exhausting of its own accord. It is a reminder that I need to also accept my grief as it is, no tears and all. There are no promises that tears would in themselves significantly alleviate my exhaustion.

They say grief is love. If my grief is also exhaustion, perhaps it is time to welcome and nurture this form of love for Neve. To expect it and make space for it, in my life. As we approach the lead up to the end of April, I have absorbed enough to understand that the coming month is likely to be arduous. What’s more, the weariness may not improve thereafter; whispers from those in the know speak of a second year, even harder than the first.

Sitting alongside my grief, as exhaustion, may need a long term plan. People talk about enfolding their grief into their life, integrating it into their being. If my grief is exhaustion, is this what I need to be doing?

It’s true, my grief is also felt in other ways: as brain fog, sensory overwhelm, inability to make decisions, anxiety, nausea, the need for quiet. But it is the heaviness of exhaustion that outweighs all of this.

Rather than a rock, weighing me down, perhaps it is my anchor, rooting and grounding me?

I am exhausted. I wish it was more widely known that this heaviness exists.

"Surely, this would have been the day for tears? Yet no, no tears came."

This is exactly how I feel as the first anniversary of my son's death came and went and my son's yahrzeit approaches (different dates, solar and lunar calendars.) Instead of tears, I feel I'm dragging a giant heavy weight around. It is, indeed, exhausting.