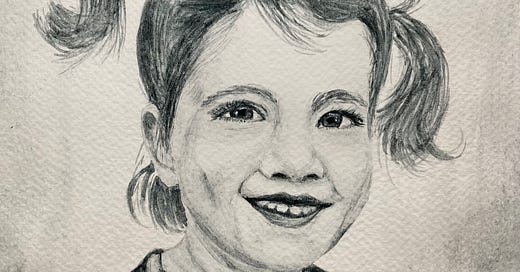

As I ponder and muse about children, I find myself slipping them into categories in a conceptual timeline of Neve’s life. A guesstimate of age and into my logbook, my classification system, they go, as I view Neve through the lens of health. The fragments of her life, the divisions, the befores and afters. Before cancer. Diagnosis. Illness. Death. And then, at the end, there is absence. Right now, I imagine absence as a small fragment, in relation to a decade of life. In time, I know that absence will grow and eventually overshadow the rest, in its expanse.

Before cancer

Neve was diagnosed with cancer at age seven. That is seven years of living, before cancer was even a notion. Or at least before we knew she had cancer. I look at small children, younger than seven and wonder what life has in store for them. It is hard to assemble my memories of Neve, before her life changed so acutely. I see children playing, innocent and unaware, light and free, and wonder how that could have been my child. How could I not have known, not have prepared myself, not have made the most of that life, before it all changed so radically. I watch my youngest, still in the before cancer fragment, and I know that the years to come, as she ages through the fragments of Neve’s life, will be excruciating. And glorious. Heartbreaking and exquisite. Bittersweet.

There is something breathtaking about watching the before. There is a dichotomy, contrasting thoughts pushing their way through my mind. A sense that we should all be grateful for health and youth, for our children. This jostles with an equally vivid knowledge that being a parent is hard, even without the added complexities of cancer. Illness and death didn’t suddenly give me eternal patience, wisdom and gratitude. It is easy to think that we should all feel every moment, enjoy the here and now, the before, because we never know what will be the after. But we are human and knowledge of pain and suffering doesn't suddenly make us into serene beings, navigating effortlessly through life.

Diagnosis

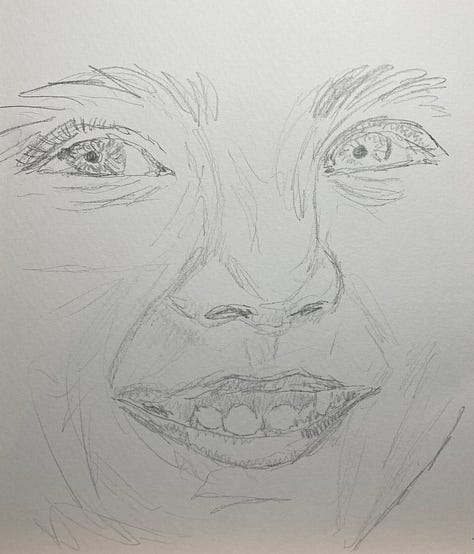

I am captivated by the age of seven, the age when Neve’s childhood, her innocence, ended abruptly. Seven year olds are little, young, naive. The nearness of their naivety, of their childishness, with serious illness, is unfathomable. I know that nobody really thinks that it will be their child but even so, it is still incomprehensible that it was my child.

This fragment is a point in time, though there is a wider, blurrier period that bookends her diagnosis. But mostly, my focus is on that weekend. July 2020. The weekend when I really started to understand that everything that I had known was about to change. When Neve was catapulted from being a headstrong child not feeling well, into being a child with a large tumour in her brain. I see seven year olds around me, playing happily and I am invaded by images of their worlds collapsing, like Neve’s did.

I revisit the moment when we had to tell Neve. It echos in my mind, grasping for the words to tell my child that she had a lump in her brain and that she would need emergency brain surgery to remove it. The sorrow and the bewilderment of doing this without professional support, of feeling utterly inadequate as a parent.

I see seven year olds and I remember saying goodbye to my own seven year old, as she was wheeled off for major brain surgery. Her little face, wide awake, aware and so full of fear and terror. Little did I know that, as she neared her death, this moment would replay itself in her mind, invading her thoughts. She remembered crying out for us and we weren’t there. There is regret, alongside an awareness that we could not have done differently.

Beyond this, there is a question that repeats itself in my mind. What did I put Neve through? The surgery, the radiotherapy, the chemotherapy, blood test after blood test. So much trauma, for such a young child. But a diagnosis of brain cancer leaves little room to manoeuvre, even when it’s a small child that it devastates. There is no easy way out.

Illness

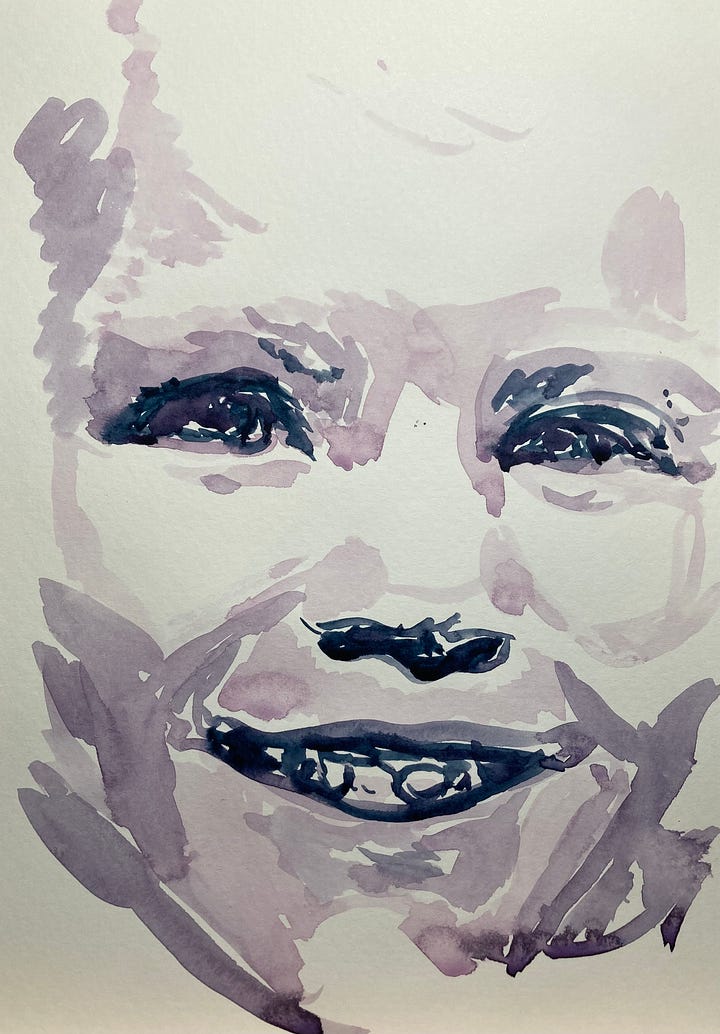

The fragment between the ages of seven and ten belongs to illness. Illness isn't really the right word, but I have no other. At the time, an unknown quantity, its borders only fixed in hindsight. No end in sight, except the one in plain sight. The illness fragment of her life transitioned Neve from a well child to a dead child.

Neve was alive in those 3 years but not living the life that we erroneously imagined. This isn’t to say that she didn’t experience love and joy, in that time, because she did. Yet close at hand, there was enormous suffering and pain and anguish. When I see children of this age, the juxtaposition of their health and vitality with Neve’s illness and sadness highlights how lonely and sorrowful her final years were.

In some ways, her illness may have masked the finality, the starkness of her death. This, while also facilitating a transition towards her death. As she grew and developed within this time, she also unraveled. A simultaneous process of growth and development and loss of abilities and de-aging.

I don’t know how to understand that time, that liminal space. Perhaps it was a time of duality. Of living and not living. Of growing and not growing. Of suffering and joy. Of life and death. When my mind pictures the ten years of Neve’s life, I see a blurry, desolate period for her final three, punctuated by glorious sparks of love and laughter. A was and was not. A presence and an absence. The scales initially tipped towards presence, but gradually tipping towards absence as time marched on.

Death

Age 10 is a transitional age. Still a child, certainly not yet a teenager but on the cusp of something. Even though Neve was desperately unwell and losing skills and abilities, she also continued to grow and to develop. I saw clear glimpses of the preteen that she was becoming, no longer a young child. My brain struggled to integrate these two ideas. How could a child become both younger and older, at the same time? Perhaps we aren’t set up to comprehend that a child will continue to grow and develop, even as a tumour marches across a brain, creating havoc as it progresses.

How can a child go from rolling her eyes at me, eating crunchy bread, making us laugh to being still, growing cold, gone? The moment of death was a shock like no other, anticipated in every way but absolutely not expected. Ten year olds are so full of life, how is it possible that life can go, just like that?

How did age ten as a transitional age come to mean a transition to death? How did I not really fully know that ten year olds die? I feel simultaneous gratitude and sorrow, for the decade that I had with my child. A decade is a gift, when I think of my friends whose babies have died. But a decade is also a life interrupted, a child just beginning to tiptoe out of childhood. It is unfathomable that Neve might have looked like the ten year olds I see around me, had she not been unwell, dying and then dead.

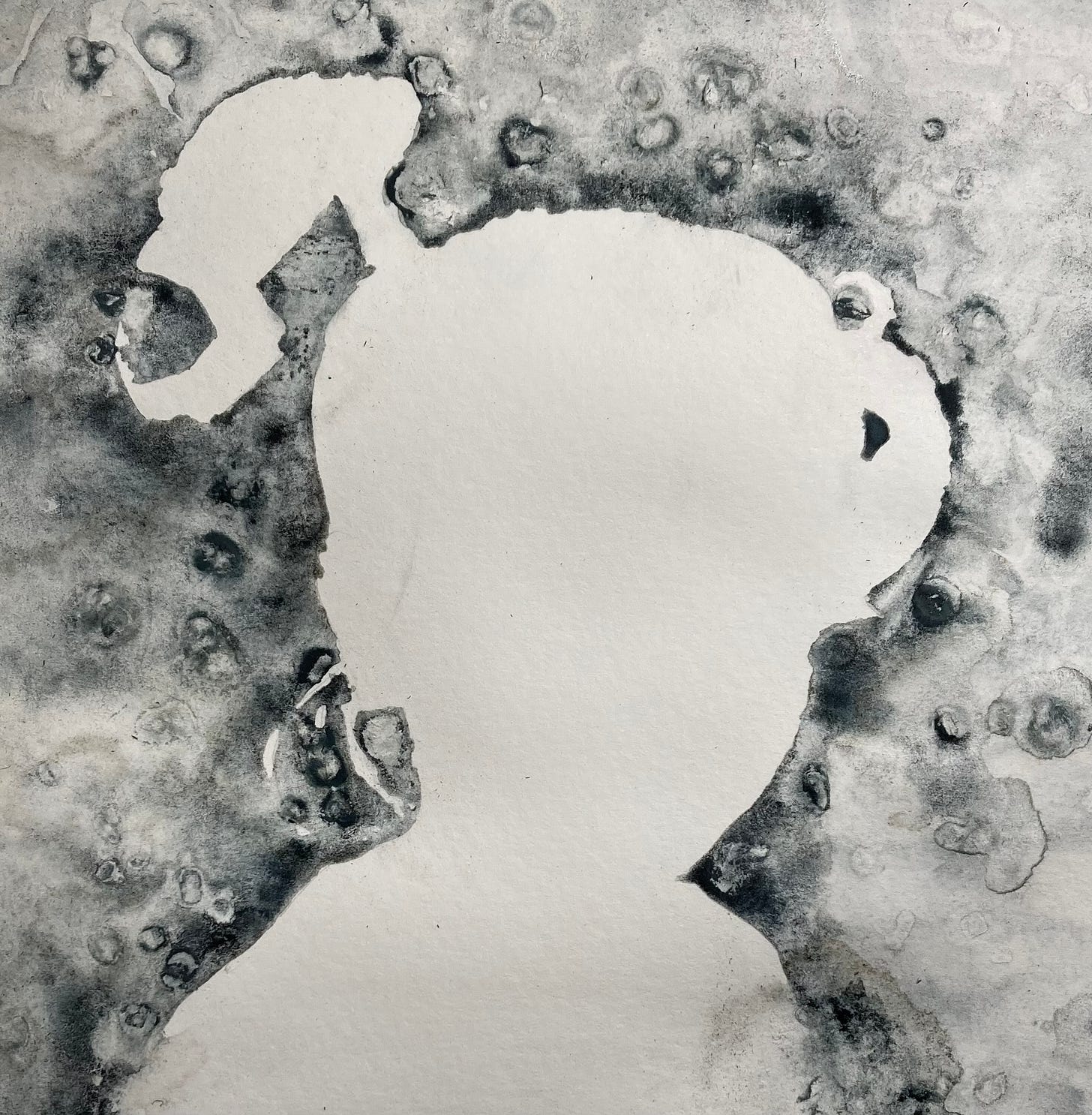

Absence

And then there is after. There is the time of absence, when Neve would have been a preteen and a young teenager and beyond. I see her friends and her cohort I and wonder. They seem so grown up. They walk to school alone, they play in the park without parents, they wear clothes that I associate with teenagers. With the period of illness being so hazy, my brain tries to grow Neve from the seven year old into the teenager. The cavernous space of illness and death hampers the fabrication of this image.

I see her friends in their final year of primary school, pondering secondary schools and I can’t really understand. How could the well Neve that I knew, the young child, how could she have been teetering on the edge of leaving young childhood behind? How can an illness create such a blur in a life, that the borders are vague yet also stark? Diagnosis was a fixed period, yet she was unwell before and her diagnosis didn’t become fully clear immediately. Equally, her death, April 30th, just after 7pm, was fixed, yet her final years were such a period of living and not, of developing and unraveling, that her illness often obscures the reality of her death.

We started to read the first Harry Potter book when she was unwell but it quickly became too complicated for her. Or maybe her brain became too clouded to understand it. As her 11th birthday approaches, I wonder whether she would be hoping for a Hogwarts letter. I wonder what happened to that space of time, how that small child could, in a different life, be dreaming of a letter of acceptance from Professor McGonagall.

How will the absence expand, in the coming years, endless, leaving Neve behind in the fragments of a short life, only blurry memories to cling to?

Hello Emily.

Thank you for your eloquent writing.

It is a beautiful expression of your love for Neve.

Your description of Neve pre-diagnosis, age seven, reminds me of Norah Jone's song Seven Years. I was most curious if you know it?

I look forward to every email you post