Hope (/həʊp/)

a feeling of expectation and desire for a particular thing to happen.

a feeling of trust

For many months, if not short years, I resisted the word hope. I felt annoyed, unsettled, when others would use it. I wondered, what do you do with such a word, when your child is dying? No longer did it feel like a word to hold, to burnish, a candle to light our way. Instead, it was barbed, cutting, a reminder that there was no future to strive towards.

You might wonder where this hostility came from. After all, hope is such a short, simple word. Two vowels, two consonants. A pattern, a balance. What’s not to like? How did I end up disliking this uncomplicated word so much?

Embracing hope

It wasn’t like this in the beginning. In the spring and summer of 2020, I certainly wasn’t pushing hope away. In fact, it had been a word to embrace, to guide us, when Neve was becoming unwell.

Initially, the hope was that a return to school was all that she needed. Structure, social interaction, her beloved teacher, surely these things would cure her of whatever was ailing her, physically and emotionally? When that wasn’t the answer, it became hope for cooler weather, for the heatwave to pass. Surely Neve was falling asleep at school and on the floor at home merely because she was hot and tired?

Then, when that wasn’t enough, and headaches were added to the mix, it became hope for something simple, benign, short-lived. Maybe anaemia or a minor deficiency, easily remedied. Gradually, it became hope for something that, although still serious, was manageable. With A&E as the next logical destination, it became hope for anything viral, for glandular fever, for Long Covid, for Lyme disease, for an answer.

We were all, doctors included, blindsided by a lesion on the brain. Whilst this wasn’t something to hope for, perhaps there could still be hope? Hope that it wasn’t a tumour, which then became hope that it was a benign tumour. This was before I understood that there isn’t anything benign about a brain tumour diagnosis. Aggressive or not, brain tumours change lives.

Emergency brain surgery came next. Certainly not what anybody hopes for. Unless perhaps you are told that a tumour is inoperable from the beginning? Thankfully, we could still feel grateful that surgery was an option and hope for a complete removal of the tumour. Then it transitioned to hope that radiotherapy and chemotherapy would do their job and keep the cancer at bay.

There were still glimmers of hope, in those early days and weeks, even if the hopes were changing as the bad news piled up. Surely there was still hope for Neve to be ok, to grow up?

What was it that interrupted my rapidly changing hopes, that caused them to fall off a cliff?

It was a bike. Neve was hoping, fervently, to get a bigger bike. This was possible, but it would mean a new bike for her biggest sister, so that all the bikes could shift down. In 2020, buying a new bike was easier said than done. How much effort should I put into fulfilling this hope? Surely, waiting until 2021, when her treatment would be done, when the supply of bikes might have returned, surely that would be the easiest plan?

This led to conversations with Neve’s medical team. This hope was important, important for Neve, I explained clearly. I needed to know, were we still hoping for a cure, could the bike plan wait until next year? Neve’s nurse nudged me forward, saying that there was still hope, but if this was important to Neve and to us, that we should probably get on with it. It was then that I began to realise that something was missing. I was hoping and they were hoping but we were hoping for different things. My hopes were false hopes, not based on reality. It was the bike that brought this lucidity.

In the autumn of 2020, I began the search for a bike for my eldest. It was around this time that I pondered a simple maths problem. I am struck now by how many months it took me to do the maths. We had been told five years, as a best-case scenario. A minority of children with Neve’s tumour are alive five years after diagnosis. Neve was 7. The maths weren’t complicated. Age 12. If she and we were very lucky. What kind of hope was that? Again, this was not what I understood a cure to mean. This was not a long, fruitful life. My awareness of how much I had misunderstood was growing.

Abandoning hope

This was the beginning of a process of untangling, of winnowing out those aspects of hope that were not desirable. What did hope really mean? Initially, at least in the cancer world that we had been catapulted into, hope had seemed to mean cure. That had been my understanding. We had been hoping for a cure, surely? The formula seemed simple: cancer + hope = cure.

This process of unpicking, of deciphering, of researching, in the context of the bike and the prognosis, led me to a clarity. I finally understood. It had taken me several months, but here I was. This understanding seared through me, again and again. That moment, just after you wake in the morning, when you remember. We were not aiming for a cure. That was impossible. The vast majority of people do not live long, healthy lives after any brain tumour diagnosis. If they survive, the long term effects of treatment are profound. And a tumour as aggressive as Neve’s? Cure felt irrelevant. But if hope meant cure, then did that make hope irrelevant too?

It was this process that led me to shun hope. Even though I had questioned and pushed back against much of the language that didn’t feel right to me, somehow I had not thought to question my merging of the word hope with cure. But now, hope, used in the context of Neve, seemed to mean false hope. I didn’t want false hope. I didn’t want to imagine her having a long, healthy life when this was unrealistic and unlikely. How could I help Neve make the most of the time that she did have, if I was distracted by false hopes? How could we prioritise Neve’s quality of life, if we were making decisions based on these false hopes?

Understanding that Neve’s diagnosis was essentially a terminal diagnosis, in all but words, was a gift. Reconciling hope, understanding that there was no hope of a cure, gave me the clarity that I needed to move forward with the bike plan.

A bike was finally purchased, bikes were shuffled up the line of sisters and at long last, it was sorted. Neve rode off on a new-to-her, big, glorious red bicycle. I look back now and feel immense gratitude to Neve’s nurse, who understood that false hope would mean Neve might never ride a big bike. Her lack of ambiguity allowed me to focus on what mattered to Neve.

But still, it felt like the wider world was holding hope up as a beacon, as an indispensable lighthouse. I felt confused, annoyed. If hope was synonymous with cure, with time, with survival, with treatment, with living, and aggressive brain tumours are generally not curable, what was the point of hoping? Why put all the energy on a cure, on hope for a cure, when this felt irrelevant? Energy and time are limited, at the best of times. I could not stop my brain from seeing the missed opportunities. Precious energy and time had slipped away, unnoticed, while we were distracted by false hopes.

Not long after this, an MRI changed everything and nothing. The biggest change was that the conversation, the words, became very clear. It was out in the open, no longer a suspicion on my part. Neve’s cancer was now inoperable, incurable, there was no more hope for a cure. The doctor’s words were carefully chosen, spoken with care and compassion. There was no more ambiguity. Another gift. Clarity. I felt and still feel deep gratitude to this doctor and his team for their bravery and their honesty.

Reclaiming hope

You might assume that my antipathy towards hope would continue to this day. Surely, watching Neve die, watching her deterioration, her pain, her sorrow, her suffering, surely that must make hope feel at best irrelevant, immaterial. You might even, understandably, imagine vexation and resentment towards this simple word.

But that is not the case. As Neve became more and more unwell, I began to wonder about reclaiming the word hope. The definition of hope, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, is “a feeling of expectation and desire for a particular thing to happen.”

Gradually, I allowed the nuances of hope to trickle in. Hope, in the cancer world, might mean cure, yes. But in the palliative care world, it was so much more shaded, refined, varied. Hope was ambitious, yes, but it was also realistic. Hope for the best, plan for the worst, they would say. Why spend precious time hoping for a cure, if that isn’t realistic?

If hope was more nuanced that I realised, why couldn’t there be hope even as death approached? Without thinking about it, we hoped for pain-free days, we hoped to reduce suffering, we hoped for smiles and laughter, we hoped for connections. We hoped for videos of Olivers and Olis juggling, we hoped for Neve to be awake when her teacher arrived, we hoped for more smoked salmon, we hoped for visits to Helen House, we hoped to stay out of the hospital. We did a lot of hoping, in fact. What we were not hoping for was more treatment. We were not hoping for a cure, because we understood that there wasn’t one.

Perhaps hope really still could be a word for us? We had had to learn to let go, somewhat, of expectations, of plans, of desires. Neve confounded and confused us all, day in and day out. At times, hope was muddled. It had to be flexible, to be nimble, to adjust. But it was there. If I focused on the real definition of hope, this was a word that could carry us forward.

And yet, there was more, more to love about hope. Upon further examination, the Oxford dictionary also defined hope as “a feeling of trust.” My smile widened. So much of our hope revolved around people, this I knew. Connection was a balm to our souls when there was suffering and sadness. Much of what we hoped for was people-focused. There would not have been much hope, had we not been surrounded by a village of people whom we trusted.

When I think about the conversation with Neve’s nurse about the bike, and the conversation with her doctor about the fact that she was going to die, I am struck by the gifts they gave us. They allowed us to hope, to properly hope, for things that were realistic for Neve. They were courageous enough to have these tender conversations with us, even when it was hard for them and painful for us. False hopes would have led us down a path of more suffering, of an ignorance of the reality, and therefore missed opportunities to focus on what was truly important.

Even when time is short, when there is suffering and pain, sorrow and anguish, there can still be hope. This hope needs to be ambitious but, to me, also grounded in reality. There is always much to hope for, even when a cure is irrelevant, impossible. For me, hope will always be intertwined with trust. Those who spoke with clarity, with honesty, those who listened, those who helped with both the day-to-day challenges and the crazy ideas that we came up with, they are where hope lay when my child was dying.

This is so incredibly moving and powerful. Your writing is so important.

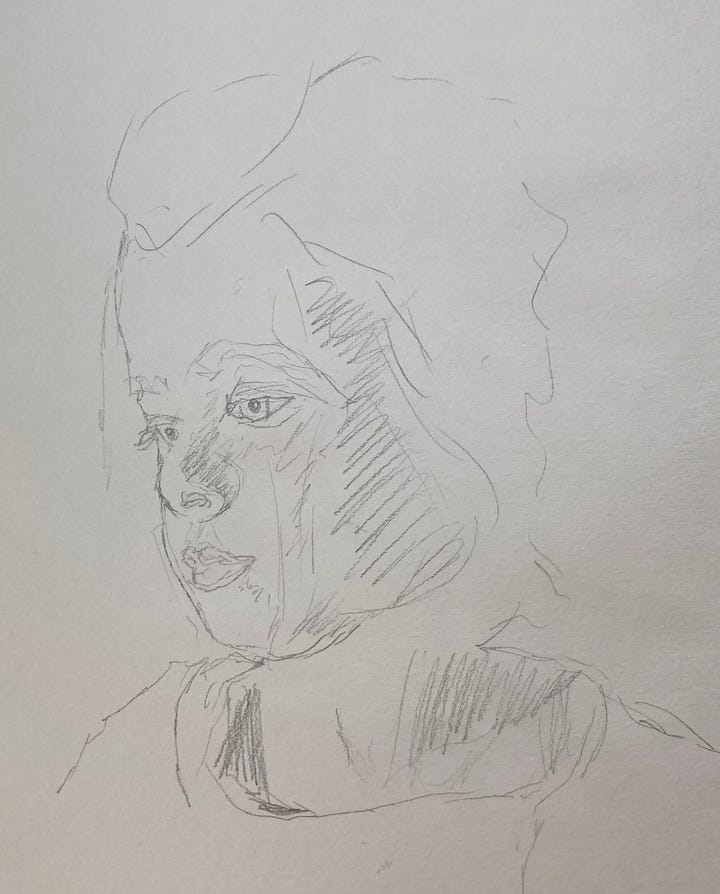

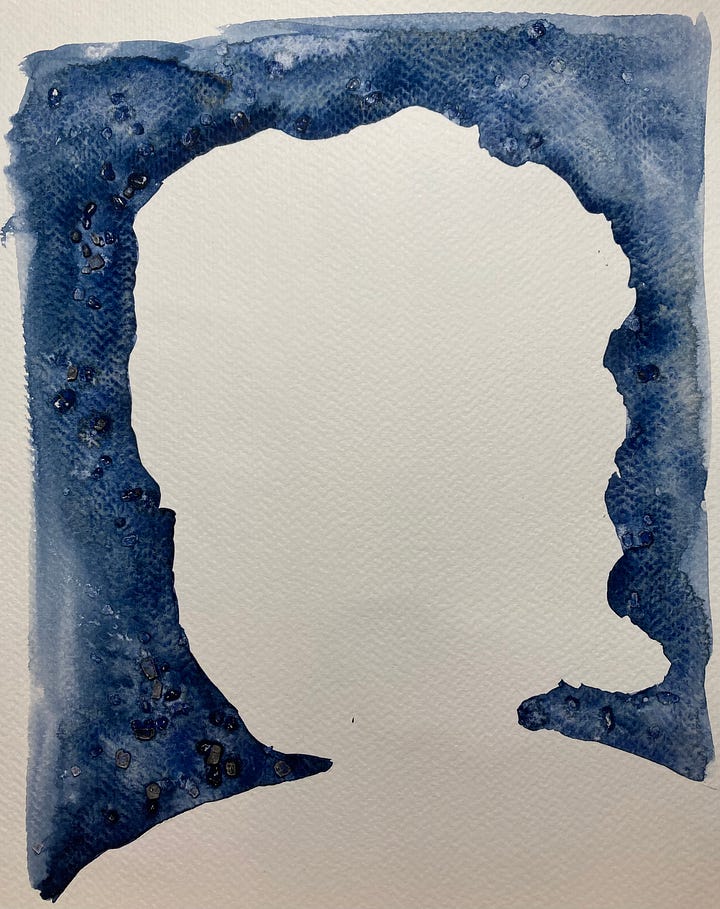

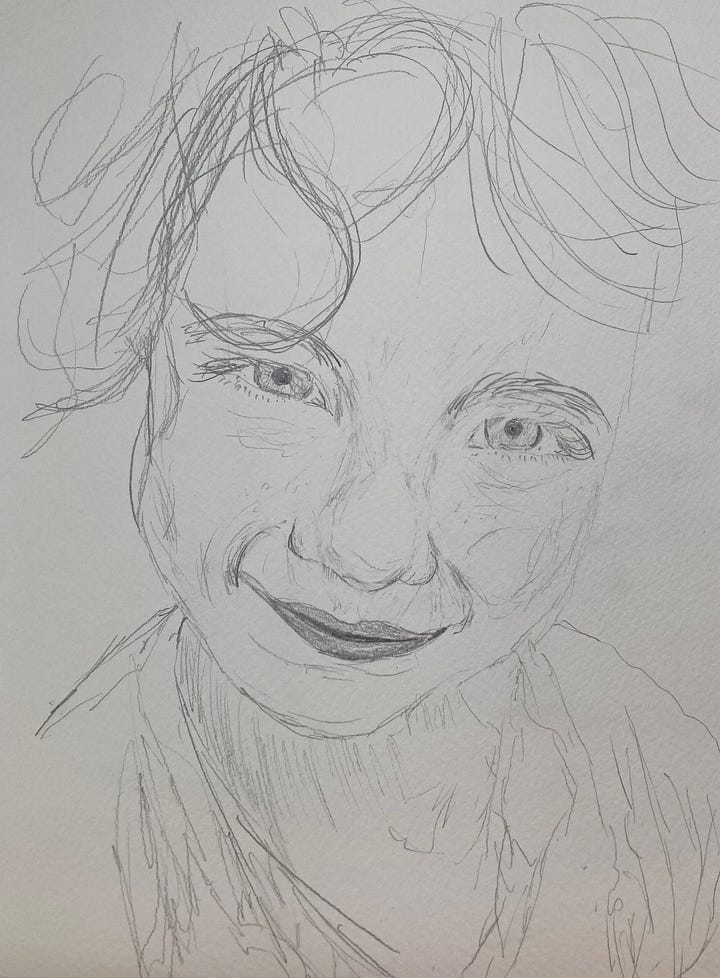

A pediatric palliative care doctor once told me that hope, by it's very nature, is never false. You can hold onto hope even when you know your child is going to die. That's a paradox but I found it to be true when my daughter was dying. This essay is beautiful and heartbreaking. Your paintings of Neve are stunning.